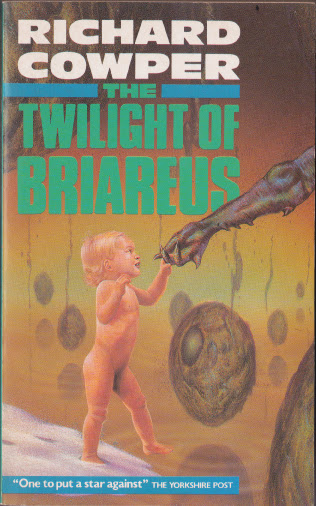

Richard Cowper’s 1974 science fiction novel The Twilight of Briareus is one of the weirdest alien invasion stories I’ve read. It made a big impression on me as a teenager, and the central idea of the book is still very strong (although when I re-read it recently its storytelling hadn’t stood the test of time). The Briareus of the story is a star 130 light years from Earth that goes supernova. When the wavefront finally hits our planet it causes immediate climatic events, including storms and tornadoes that lash the British coastline, and the slow onset of a mini ice age. But that’s only the visible effects. Soon it’s discovered that the entire human race is now sterile, and certain people – including children conceived at the time of the Briareus event – have telepathic abilities. One scientist begins to suspect that alien entities have used the supernova to take over humanity…

It struck me on first reading as a very ‘left field’ concept, so it was interesting to read the latest studies about an actual event that occurred in our galactic neighbourhood during human pre-history. Two supernovae exploded several hundred light years from Earth about two million years ago, leaving radioactive traces that can still be detected on the ocean floor and the surface of the Moon. It’s been theorised that both these events could have affected the development of homo erectus, who was busy descending from the trees at the time.

Certainly the increase in ambient light – the supernovae would have been as bright as the Moon for at least a year – would have affected the behaviour of animals that take such cues to navigate or mate or lay their eggs; and we can only wonder what our ancestors made of it, perhaps inventing stories of sky gods and titanic battles in the heavens. Luckily the wave of radiation that followed – approximately five hundred years later – was relatively weak, raising background radioactivity to only three times what it is today. That’s a small amount, likely to increase the risk of cancer, for example, by only three per cent.

So we dodged a bullet two million years ago. And in case you’re wondering, the risk of another nearby supernova happening today is less than one in several billion.