For me, the key to ‘worldbuilding’ is what your characters take for granted.”

Ian MacDonald, author of Luna and Brasyl

On the face of it, worldbuilding is closely associated with science fiction and fantasy. Think of the millennia-spanning mythology of elves, dwarves, ents and human tribes that informs JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings books, or Iain M Banks’s Culture Series with Ship Minds, rich and diverse planets and societies and galactic-level political manipulation. Certainly worldbuilding is vital to these types of stories, not just in creating a believable immersive world but also – and this is a point of difference from many other types of writing – to create a ‘sense of wonder’, which is a keystone of fantastic fiction.

But worldbuilding is just as important to every other type of fiction you can imagine. Think of worldbuilding as being everything in your novel that provides a framework for your characters and plot to move through. The decision to set your crime novel in contemporary times – with ubiquitous access to mobile phone technology – will affect the actions of your characters, how they discover key clues, and how difficult it is to conceal anything that happens in the public sphere. Transplant your story to Victorian London and it will evolve and be supported in a very different way.

So where do you start? Particularly with science fiction set in the far future where you can’t rely on contemporary political, technological or even environmental elements that are familiar, how do you create a whole universe with everything from power generation and mass transit systems right down to what people eat for breakfast?

The answer is you need to be selective: concentrate on those things that matter and suggest the edges of everything else. In popular fiction, everything that appears in your book should in some way serve to progress the plot. So if your characters or plot never have anything to do with public transport, you don’t bother with it, or mention it only in oblique terms.

Also, your world doesn’t need to spring fully formed from your imagination as you write your first sentence. It’s true you need to make some key decisions before you start – and these may be subconscious or conscious ones – such as what time period your story’s set in and who your protagonist is: where do they come from and what is their history? This shines a light on the immediate vicinity of your world, and from there you can push that light outward and discover more of the space your characters and plot are living in.

My current work in progress – the Lenticular Series – centres on an alien whose world is invaded by a cruel future-human empire called the Hegemony. When I started I knew I wanted my alien species to be empathic – that is able to sense the emotions of others – and for the humans to rip that ability away from those they captured to create a group of outcasts in order to divide and conquer the species. I needed rules about how the empathic ability functioned and how it could be removed without killing the individual. I also needed to work out how an empathic society might function. Being universally lovey-dovey doesn’t make for an interesting plot; I wanted my aliens to be involved in political infighting before they were invaded.

These decisions led to a number of questions that needed to be solved. If there are different groups of aliens, how are they organised, how do they stop rivals reading their emotions, how do they divide up the landmasses on their planet (which led into questions about the different geographic areas and climates of their homeworld), how do they create wealth, who are the winners and losers? The beginnings of this framework led into questions about the plot. If there are losers in this society, what are they doing to rebalance things in their favour? How is that disrupted and who takes advantage when their world is invaded by the Hegemony? By answering questions like this the plot gains depth and texture and weight.

Not all worldbuilding is done up front. Sometimes the plot suggests a gap or a problem that can be solved by bolting on another piece of your created universe, like inventing some history that explains why the Hegemony is evil. A species can’t just be ‘bad’. Not only is that boring, it’s not realistic. Something must have happened that frightened the humans so much on an existential level that they see invasion and subjugation of others as necessary. I’ll leave the reason for that for you to discover when book 1 is finally published.

The other part of worldbuilding – and for me this is the really fun bit – is working out how things look in your novel. Think of it like making a movie. You need makeup, costumes, props, rooms and buildings and landscapes to move through. Different alien species must look different, have different types of spaceships, different levels of technology, dress differently, eat different things. Their worlds are different and the places they visit on their worlds have to be ‘real’. Or you have to describe them as if they are. That’s where the internet – and in particular Pinterest – is useful.

It’s hard to visualise stuff that doesn’t exist – at least for me it is – so I find it helpful to create ‘mood boards’ for places, characters, ships and technology.

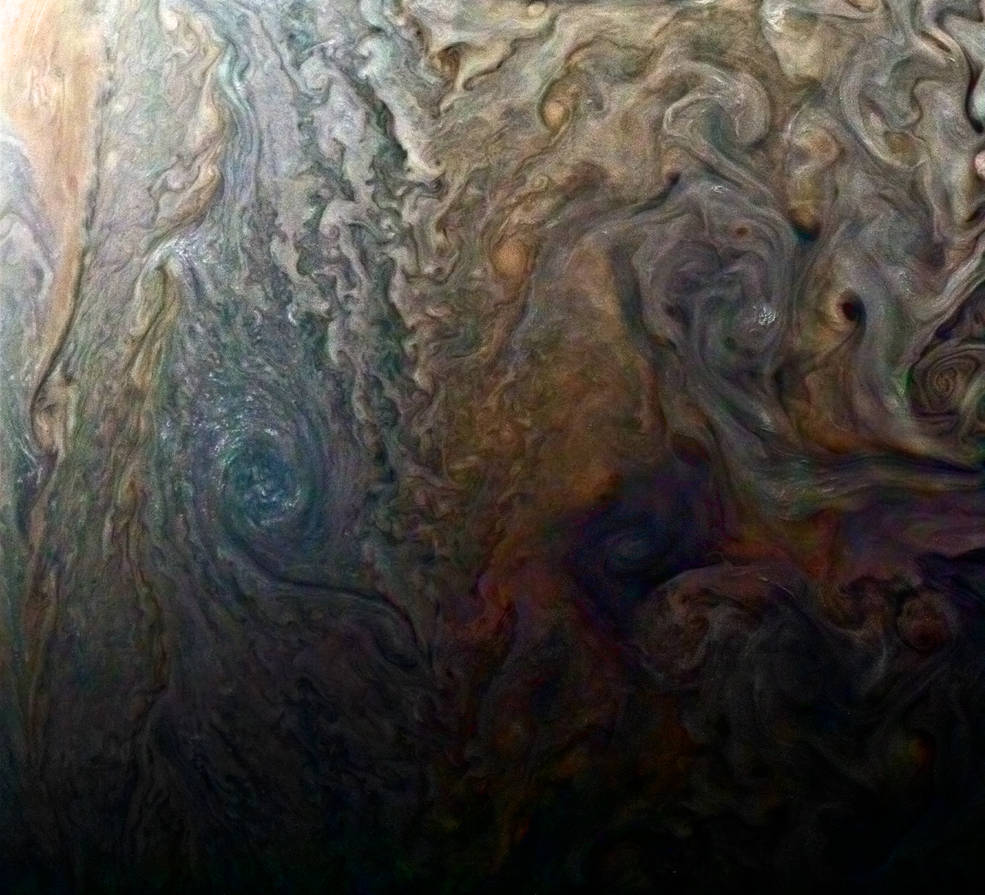

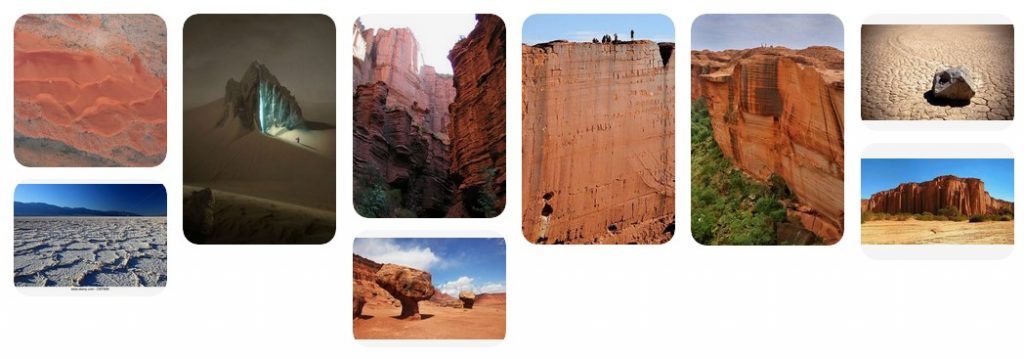

Most of the boards I’m creating for the Lenticular are still private, but this board https://www.pinterest.com.au/keithstevensonw/homeworld/ has helped me visualise the key sites on my alien’s homeworld.

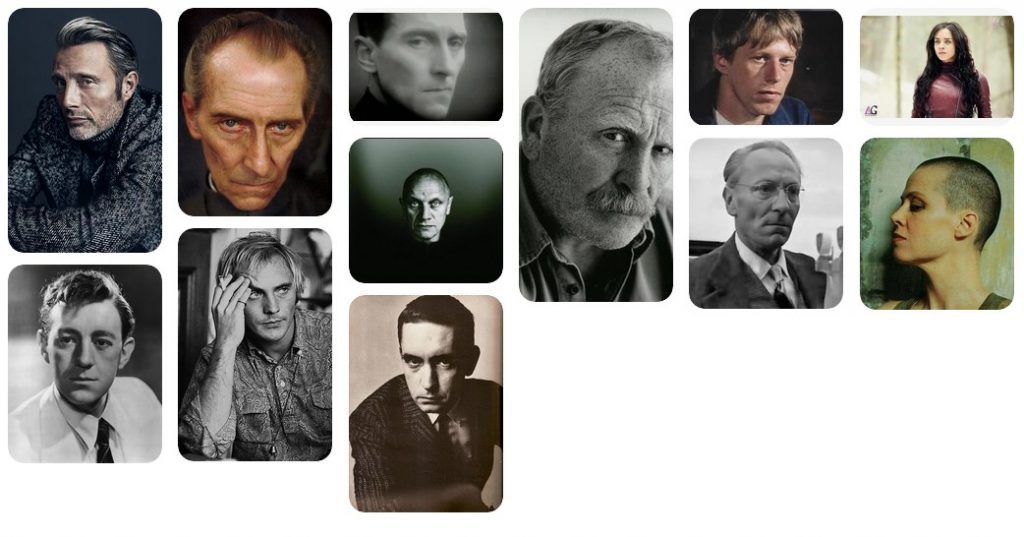

I also have a character board for Hegemony political figures, which is a useful visual shorthand for me when I’m writing these people, not only to keep the physical details of my characters sharp but also the ‘feel’ of the type of person they are.

I have boards for ships, technology and clothing (particularly wearable tech that I’m using for my Hegemony soldiers) and alien environments and landscapes. All of it helps my writing to be more detailed when it comes to descriptions of things and places (and more consistent if I revisit places at different points in the books), and hopefully this makes the reader’s experience more immersive.

However, you don’t want your novel to get bogged down with worldbuilding detail. Individual words can be powerful too. If you describe a ship as a ‘lozenge’ or a ‘horseshoe’ or a ‘torus’, the reader can visualise it without the need to go into lengthy description. SF author Alistair Reynolds does this a lot too: my favourite word of his is ‘medichine’ for the molecule-sized robots that live in people’s bloodstreams to keep them healthy.

The key thing to remember when worldbuilding is that everything has to serve the plot, not get in the way of it. A lot of your worldbuilding won’t expressly appear in your books, but the ideas and feelings that research has presented to you will be there in how you think about things and how your characters interact with where they are, what they see and what they take for granted.