In my post Engage engines, I talk about the theoretical drive that boosts the explorer ship to an appreciable fraction of the speed of light in order to reach the Iota Persei system in a reasonable time — i.e. before my ‘stellarnauts’ grow too old. But the drive is only one part of the ship, which has to provide space, life-support and light for the stellarnauts inside, possibly for decades. So what does it look like?

In general configuration, the outside of the Magellan is a stubby cone packed with everything the crew need. The hull is metal, of course, but covered with ice, just one defence against a myriad of dangers, as Mission Leader Cait Dyson knows.

The Pax Americana ship Magellan fell steadily towards Iota Persei and its retinue of planets. Its hull was coated in a thick mantle of water-ice. Cait knew the interplanetary ‘vacuum’ was anything but empty. At 0.6 light speed, even a tiny fragment of rock crossing their path could cause major damage. So far, statistical probability had been on their side. But serious collision was only one of a million things that could kill them without warning. She’d been appalled at first and then finally bored by the seemingly endless catalogue of hazards laid out in the mission pack. Looking at Bren now, though, she couldn’t shake the feeling the list may not have been as exhaustive as she’d thought.

The main habitat area is a large drum rotating within the hull to create a faux gravity due to centripetal force. Cait and her fellow crewmembers spend most of their time inside as long-term exposure to weightlessness not only causes loss of bone density but muscle wastage as well. Even with the drum, the crew are in less than peak physical condition when they awake from their long deepsleep. So what about the rest of the ship?

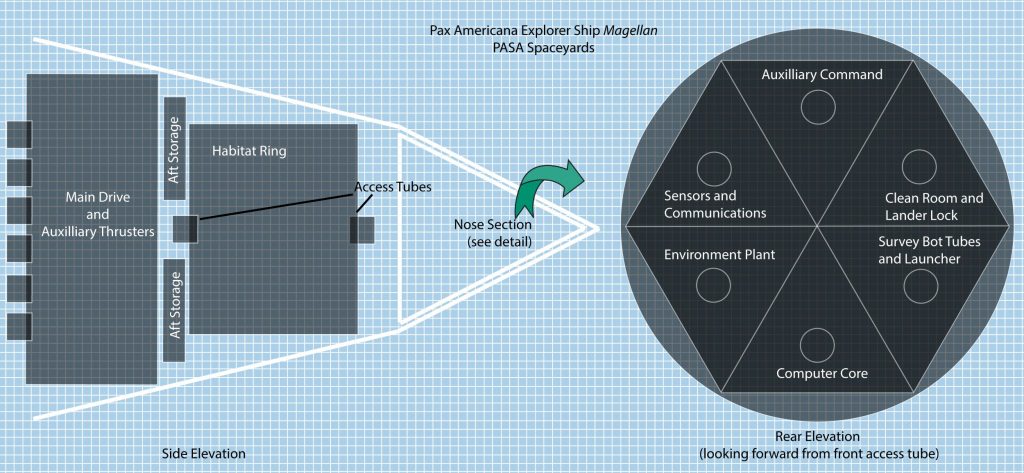

The port still flagged computer and life support. She cleared the screen with a wave and began checking internal sensors, bringing up a schematic of their craft. The familiar stubby cone of the explorer ship Magellan flashed up in cross-section and she worked the sensors from stern to stem. First came the thickest portion, the massive hold containing the zero-point drive, partially open to the vacuum. Next the aft storage area, hard up against the revolving drum of the main habitat ring. Nothing. Hull integrity, atmosphere, ambient temperature, servos, relays, all okay. Ahead of them was the fore access tube and the six segmented bulkheads of the forward section tapering towards the nose: auxiliary command, clean room and lander lock, bot tubes and launcher, computer core, environment plant, and long- and short-range sensors and communications — each segment lined with additional storage bins wherever clearance allowed. There was nothing out of the ordinary. Which meant whatever had gone wrong was outside their ability to easily define.

Of course not all of this is ‘important’ to the story but, as I mentioned above, the props are vital in sci-fi and the author has to do a lot of work to imagine the smallest detail so they can speak to the reader with authority about how the ship functions and how the crew moves through it. That’s why I created a schematic to help me plot the action and movements of my crew through the interior of the ship.

Welcome aboard. I hope you enjoy the trip more than the crew of Magellan do.

“Picture credit: Spaceship Corridor” by asmoth360 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0