This is Udun. He’s a Kresz from a part of space called The Lenticular, which holds many alien civilisations. He stands 2.4m tall (normal for his caste, but shorter than most Kresz females and certainly shorter than Defender caste Kresz) and has both an endoskeleton and a chitinous exoskeleton like laminate armour. His body plan is typical for a member of the scholar caste. He has three claws on each hand, and as a result the Kresz have a base six numbering system. In fact six is a very important number in Kresz society: six houses with six leaders (or hierarchs), six lodges with six deans who control the main forms of employment: trade, agriculture, defence, learning, technology and the priesthood; and six social castes ruled over by the council of hierarchs and deans.

The fleshy projection that looks like a cobra hood behind Udun’s head is what gives the Kresz the empathic ability to read the emotions of other Kresz. It’s not something Udun enjoys because it exposes him to the disapproval of others – disapproval of his desire to travel out into the stars and meet other species, which is a very un-Kreszlike thing to want. But even Udun wouldn’t ask for his mantle to be severed from his body, which is what the Earth Hegemony does to countless Kresz when they invade.

This is just a snapshot of Udun and the Kresz species. There’s far more detail on both that I could share. While it’s true to say that creating believable, well-rounded human characters is quite an art, doing the same for a non-human character requires even more work.

For a start, the reader needs to believe the character is a non-human. They need to be able to understand and picture the character’s alien physicality as clearly distinct from human form. That’s not something a writer needs to worry about with a human character. They simply needs to provide a character description based on physical attributes that already exist.

The reader also needs to feel that an alien character ‘acts differently’ to humans. That they have a different set of responses to humans based on their different mental architecture, upbringing, and the views of the society they were raised in. The same can be done with a human character if the writer wants them to present as unusual, but most human characters have human reactions and if they have a different upbringing it’s either because they come from a different country or part of the country or they were raised differently, for example within a commune or religious sect.

The body of the alien

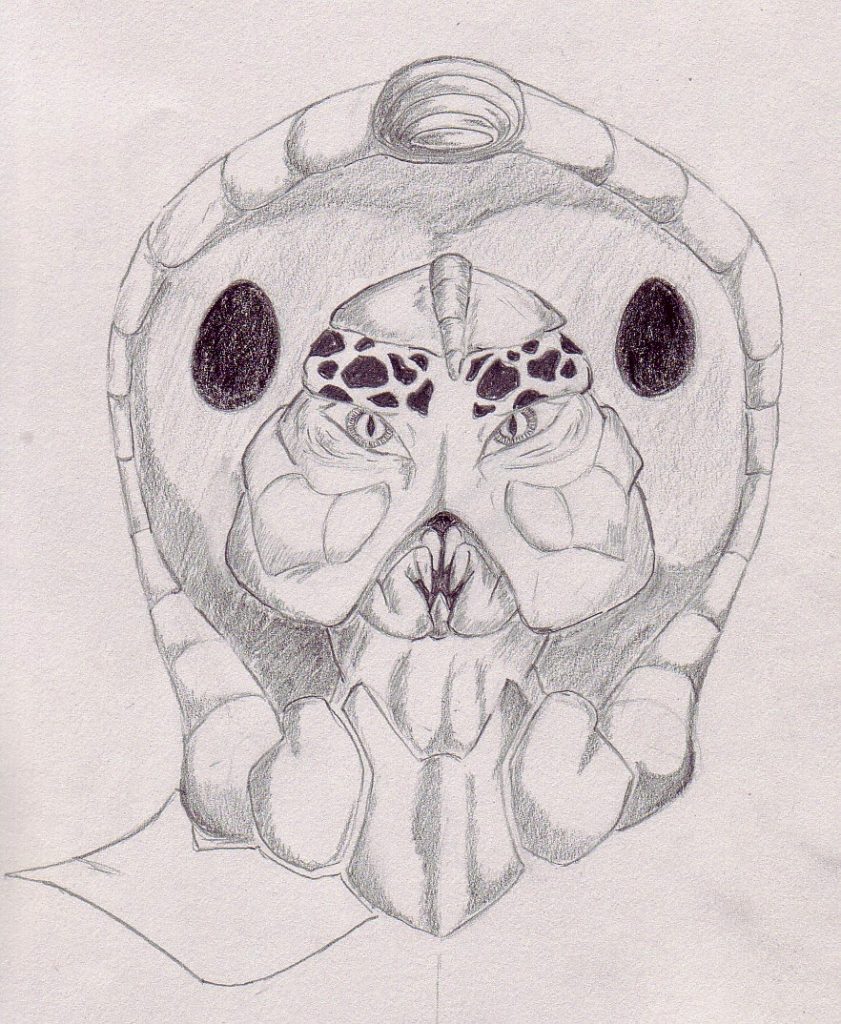

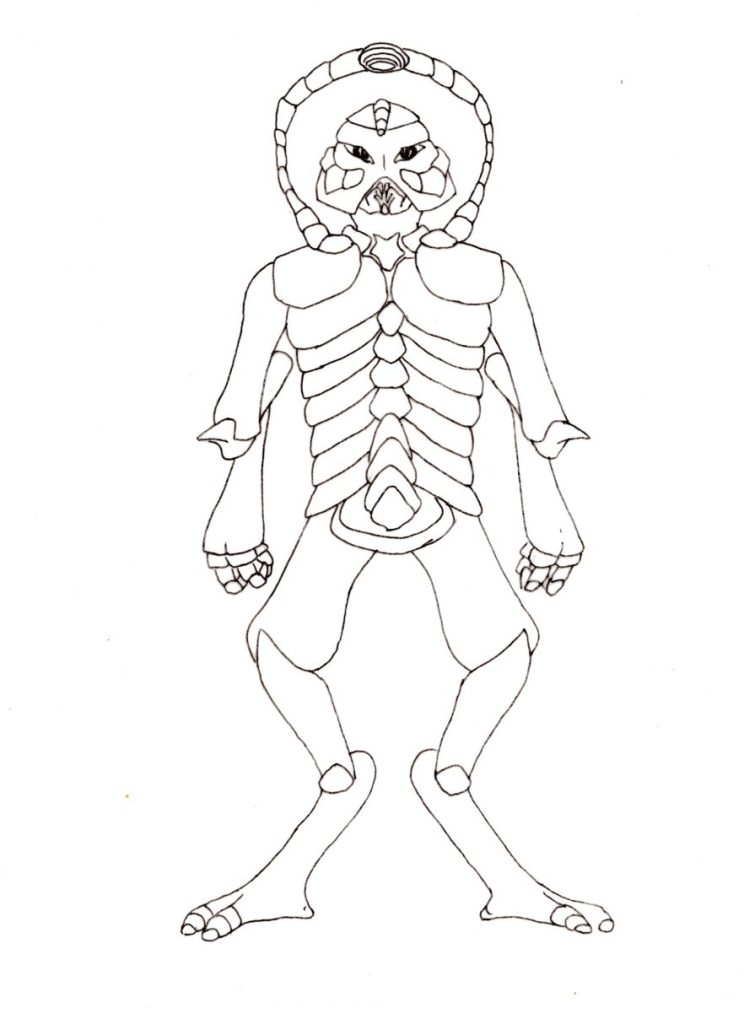

Different writers will use different methods, but for me I had to work visually to imagine Udun and the other Kresz. The picture above was the first sketch I perfected of a Kresz. I wanted something alien but not too outlandish. You’ll see there’s a humanity to the eyes. The Kresz aren’t monsters. They may look scary at first but if you get past that, the eyes help you understand they are thinking and feeling beings (though most Hegemony troops wouldn’t agree, but that’s their problem). I sketched the head and shoulders first, but then I needed to know what the Kresz body looked like. That’s when I came up with this picture:

This was important not just to help describe their overall physicality, but so I could label and describe their different body parts in a way that emphasised the non-human. So ‘claws’ not ‘fingers’, ‘hoofs’ not ‘feet’, ‘shoulder plate’ not ‘shoulder’. That consistency of description in the prose helps the reader remember the alien nature of the character in a simple yet powerful way.

You’ll see the chitinous plates make their torso resemble a lobster or a crab. Crustaceans along with spiders, scorpions and insects like locusts and so on belong to a class of animals called arthropods. To build more alien physicality, I decided to look at arthropod physiologies. That’s why the Kresz have spiracles, which are like small air tubes dotted all over the skin which feed oxygen directly to the tissue (and are common to many arthropods). To augment this – because Kresz are much larger than insects – they also have a number of ‘book lungs’, like locusts, spiders and other arthropods, which pump oxygenated fluid round the body. This gave me the idea of Kresz having a lot of built in redundancy in their physiology, because of environmental and historical factors, which means they can survive major trauma that would kill a human, such as losing multiple limbs.

I also decided that the Kresz body would be specialised for different tasks, so Defender Kresz are huge juggernauts with a dominant and massive pincer claw instead of one hand (just like some crabs have one pincer larger than the other), agricultural workers would have elongated limbs to help with harvesting, and adepts would be generally shorter with smaller claws and feelers for delicate work.

More animal research also helped me come up with the idea of a two-stage insemination process for Kresz mating – loosely based on bees – with the idea that the hierarch is required to undertake secondary insemination to determine the body type of the subsequent Kresz youngling.

The hard shapes of the Kresz mouth feeders also helped me imagine the sounds they could make, which led to a list of Kresz phonemes I used to create all Kresz names and words – which made those words sound like they all came from the same authentic spoken language.

The six claws leading to a base-six numbering system was an obvious twist on our own ten finger/ base-ten system and I fell down a rabbit hole working out how the base six numbers were expressed in dialogue as well as creating a base six time system.

Telling all this detail in a novel would be incredibly dull but – as with all worldbuilding – it’s important as a writer to know how the imagined world works so small details can be woven into the narrative to give the reader a sense of being there. I did however create an imagined report written by a Hegemony Diplomatic Corps officer after the clandestine capture and ‘destructive interrogation’ of a group of Kresz, which carries a lot of information about the Kresz and which appears at the end of Traitor’s Run.

The empathic ability

The key element of alienness for the Kresz is, of course, their empathic ability. This is a physical feature as well as a psychological attribute, which also feeds into how they react/ interact in society.

Physically, it’s pure invention, a piece of flesh across the shoulders that ‘somehow’ enables the Kresz to feel the emotions of others. But there needed to be logical rules for how it functioned. Proximity between Kresz was an obvious way to enhance the empathic ability, working in the same was as hearing. Touch was another obvious way to increase the ‘depth’ of connection between Kresz. But I wanted a way for the Kresz to go deeper at times and experience a true sharing. That’s where the idea of the ‘Communion’ came in.

When two Kresz touch and their mantles become engorged they enter a private Communion space where they experience the self as other and the other as self. Similarly, when a group of Kresz collectively raise their mantles they experience another form of Communion where the self falls away to be replaced by whatever the group’s focus of concentration is on.

The empathic ability is not something that can be switched on or off, so this ability would also bleed into dreams and the unconscious of the individual Kresz. That’s how I imagined the ‘worldmind’ a dreamspace for the Kresz that reflects the collective unconscious.

From a psychological point of view, the empathic ability is like an additional form of communication and its effect on the psyche is just as fundamental as speech and hearing. It is a basic way that the Kresz use to connect with one another. So when the Hegemony comes in and removes this ability it’s as damaging to the individual as suddenly going mute or deaf or blind.

Since the empathic ability is such a defining element of the Kresz species, it was also a key way to give Udun a point of difference as a protagonist from the other Kresz. His wanderlust is a very non-Kresz trait and when other Kresz learn of it, he feels their disapproval, which in turn makes him want to turn away from the empathic sense. This allows him to function individually off-world and makes him stronger than other Kresz when the invasion occurs.

The alien mind

There’s a whole spectrum to how alien the mind of a non-human character can be. SF author CJ Cherryh is great at depicting this, and one good example is her Chanur Series. In the books, The Compact is a loose trading alliance between seven alien species. The Hani, the Mahendo’sat, the Stsho and the Kif get along fairly well – or if not well, they can at least understand how each other thinks, and can predict how a member of one of those species will act in a given set of circumstances. Even among these aliens, however, there are intellectual or social ‘blind spots’, and this is where misunderstandings and opportunities arise. So, for example, the Kif can’t understand the type of deep loyalty than exists within and between Hani clans. A Kif would turn on and betray a Kif ally without a second thought. They can’t understand that a Hani would die to protect another Hani to which they are loyal. In the right circumstances that can give the Hani an advantage over the Kif.

The other three alien species in the Chanur Series are the T’ca, Chi and Knnn. All of them are methane-breathing aliens and their frame of reference is so different from the other aliens in The Compact, none of the other species can really understand them or predict what they’re going to do. For the reader, these aliens are simply agents of chaos, unable to be understood in any meaningful way.

The role an alien plays in a novel determines how ‘alien’ they can be. Clearly a novel where a Knnn was the main protagonist would be completely impenetrable to a human reader. There’s no chance the reader could understand their actions let alone identify and empathise with them. So because Udun is one of my main protagonists in The Lenticular Series, the Kresz need to think and react in a way the human reader can understand. But they still need to ‘feel’ alien to the reader. They can’t just be humans in alien looking bodies.

In the case of Udun, that non-physical alienness comes from how the Kresz society functions. To deepen the trauma of the Hegemony’s removal of Kresz hoods, I decided that the Kresz had a deep-seated drive towards the physically perfect. This came from a belief system where their ‘creator’ set them on a path towards perfection. The practical upshot of this is that any Kresz who was born deformed or suffered a debilitating illness or injury was euthanised and – consequently – the Kresz species never developed medical practices or medicine. That’s quite an extreme set of circumstances from a human point of view, but Udun – raised in that society – see it as ‘normal practice’. Additionally when a Kresz dies, the ‘funeral ceremony’ ends with the body being split open and the attendees sampling some of the dead Kresz’s flesh so that their essence can rejoin the body of Kresz society. Again, a very alien behaviour but presented as completely normal by Udun and the other Kresz that participate in such a ceremony. And it’s in this way that the ‘alienness’ of Udun is maintained in the mind of the reader. There are, of course, other aliens in Lenticular space that are less understandable to the reader and to the Kresz alike.

As well as being an alien, Udun also needs to function as an individual. And that means he needs something to push against. As mentioned, his wanderlust is something very non-Kreszlike but it’s a core part of his being. Because of it, he’s able to undertake a secret off-world mission for his hierarch, which leads to knowledge of the Hegemony and the danger it poses to Homeworld. But more broadly the Kresz society is at a crossroads as personal freedom of a growing population begins to press against the hidebound conservative structures of the houses and lodges. The stage is set for change. Whether it’s change for good or ill remains to be seen.

Traitor’s Run, book one of The Lenticular series is currently available for pre-order from 1 July with a publication date of 1 October.